Urban Education - Day 1

UH PhD CUIN 2018-2019

Last Monday our first classroom was really interesting. It´s amazing how education can be "labeled" according to the setting, conditions, needs, culture, people, economy and many other situations when and where it takes place. This subject is about Urban Education.

After reading some of the articles in our classroom and our conversation I would like to share all this with you all:

Education is a fundamental

human right, which must be able to be exercised by all the inhabitants of a State, whatever the area where they are located. However, according to the U.S. Constitution education is not a fundamental right but an ‘important service’. Every state (with the exception of Hawaii) has relied heavily on

local property tax revenues to fund public schools. Such a system amounts to socioeconomic-discrimination, as more affluent school districts with more businesses and higher residential property values have been able to raise more money from local sources than poorer districts.

Before its definition I´d like to share with you an interesting point that we mentioned in class but another author did too: what do people think about what Urban Education is?

In this

article the author summarizes the different opinions by a personal poll:

"The general perception (based on personal survey) of an urban educational setting is as following:

Based in an urban metropolis (Los Angeles, Miami, Dallas, New York City, Chicago, etc)

Varying student demographics (Immigrants, low-income, low socio-economic status, etc)

Generally poor student behavior and involvement; high pregnancy, drop out and crime rates

Limited academic success and background of students

Limited involvement of parents

High teacher turn-over rate; unable to handle urban school setting

Run-down campus, limited budgets, and large class sizes

“No one cares”mentality

School located in poverty-stricken neighborhood, high crime rates, influence of gangs, etc.

Generally associated with specific demographics: Hispanic and African-American

The author also shares another opinion:

“Many Americans believe that urban schools are failing to educate the students they serve. Even among people who think that schools are doing a good job overall are those who believe that in certain schools, conditions are abysmal. Their perception, fed by numerous reports and observations, is that urban students achieve less in school, attain less education, and encounter less success in the labor market later in life” (Lipman, Burns, and McArthur, 1996).

What is Urban education?

According to the website

Enciclopedia we can read the definition of urban as

"...is simply "a term pertaining to a city or town." In everyday parlance the term is used frequently to distinguish something from the terms rural, small town, suburban, or ex-urban. These objective size and density definitions, however, do not convey the range of meanings intended or received when the term is most commonly used. Perceptions of urban areas differ widely."

So there are generally two ways to take into account its definition:

- as a spatial context (geography), by identifying what happens within this framework but without considering that it has properties likely to impact significantly from which goes to the educational level

- as a social process, where it is considered that the educational activity is embedded in a tissue of social relations that are primordial to decipher in order to understand what is happening in education.

Education in an urban environment is basically attached to the concept of geography, taking into account all the circumstances and situations that affect its overall system, the context and the particular social processes inherent to the site effect, which is never neutral.

When did Urban Education appear?

The concept of U.E. is parallel to the growth of urban areas. During the first half of the 20th century urban areas were viewed by many as economically dynamic, attracting and employing migrant populations from small towns, rural areas and abroad. During the second half of the 20th century however the term urban became a pejorative code word for the problems caused by the large numbers of poor and minorities who live in cities. Such negative perceptions of urban profoundly affect education and shape the nature of urban schooling.

Urban education offers many more opportunities, because there are more schools, which adapt to a massive enrollment, with more technology, better teachers (since few want to resign the convenience of working in cities to do it in remote places, with little or complicated communication through public transport, and with very little salary difference).

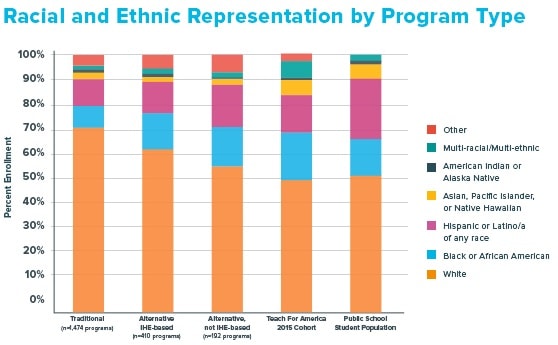

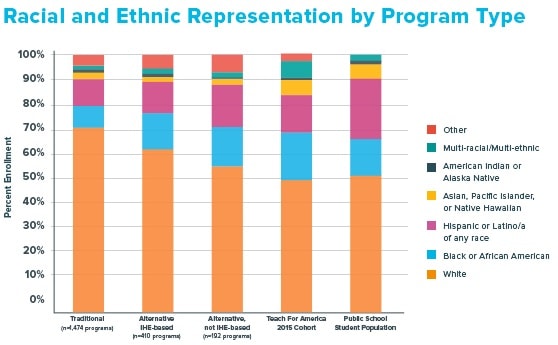

Both pictures belong to the article "Increasing Racial Diversity in the Teacher Workforce: One University’s Approach" (

pdf version)

Another image that that reflects the country’s public-school student population:

|

SOURCE: 2014 U.S. Department of Education, Higher Education Act Title II State Report Card System (AY 2012-13 data)

SOURCE: 2015-16 Teach For America Official Statistics Report “Corps Size & Demographics: 2015-16”

SOURCE: 2012-13 U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data |

As a possible solution to the diversity of the classrooms we can read the following excerpt from the

article "Student Diversity, TFA, And The Teaching Workforce: What The Numbers Tell Us":

"TFA is committed to dramatically increasing the diversity of America’s teacher workforce across multiple dimensions. We work to recruit accomplished individuals with a variety of backgrounds and experiences, including teachers with STEM expertise, LGBTQ teachers, military veteran teachers, teachers of color, and teachers with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status."

In this article the Association of Teachers for America analyzes the diversity in US public schools, and as we can read above, to deal with the diversity in schools districts decided to start hiring teachers that belong to this diversity too.

What are the challenges in U.Ed.?

In the

article Urban Education:

The State of Urban Schooling at the Start of the 21st Century by the

The Haberman Educational Foundation we have a list of its challenges:

1. Highly Politicized School Boards.

Board politics in major urban school districts often impede judicious decision-making (Ortiz, 1991) Two practices are particularly dysfunctional. First, in an effort to better represent diverse constituencies, citywide board seats have given way to narrowly drawn district seats. Board members elected from such districts may find it difficult to support policies and budgets aimed at the good of the total district when doing so is viewed negatively by parents, citizens and educators in their own neighborhood schools. Second, board members too frequently try to micromanage large, complicated school organizations thereby abrogating the leadership and accountability of their own superintendent. Finally, it is not unusual for narrow majorities on boards to change after a board election and for a superintendent to find his/her initiatives no longer supported and even have his/her contract bought out.

2. Superintendent Turnover.

The average years of service for an urban superintendent are 2 and 1/3yrs. (Urban Indicator, 2000). As a result a new superintendent may function more as a temporary employee of a school board than as the educational leader of the district and the community. Administrators and teachers are reluctant to throw themselves into new initiatives that are not likely to remain in place long enough to show any results. Constituencies (governments, businesses, church groups, foundations, universities, etc.) with whom the superintendent must interact may take a wait and see attitude rather than become active partners in the new superintendent’s initiatives.

3. Principals as Managers and Leaders.

The size and complexity of most urban schools inevitably lead to a focus on the principal as the manager or CEO of a major business enterprise. This emphasis has led to a transformation of the traditional principal role as an instructional leader. (Haberman, 2001) Few urban districts dismiss principals because of low student achievement unless the achievement falls low enough for the school to be taken over by the state or district and be reconstituted. In practice the typical urban principal who is transferred or coaxed into retirement is one that has “lost control of the building.” The district’s stated system of accountability may place student learning as the highest priority but the real basis for defining urban principals as “failing” is not because they have been unable to demonstrate increasing student achievement but because they have been unable to maintain a custodial institution. The fact that most urban principals spend the preponderance of their time and energy on management issues demonstrates that they fully understand this reality. (Kimball & Sirotnik, 2000)

4. Government Oversight.

Local and state government officials involve themselves more and more in educational policies that impact urban districts. This politicization of education produces an endless stream of regulations and funding mechanisms, which encourage or penalize the efforts of local urban districts. Like an overmedicated patient the treatments frequently counteract one another or have unintended negative consequences.

5. Central Office Bureaucracies.

In rural, small town and suburban districts, classroom teachers comprise 80% or more of the school district’s employees. In the 120 largest urban districts the number of employees other than teachers is approaching a ratio of almost 2:1; that is, for every classroom teacher there are almost two others employed in the district ostensibly to perform services which would help these teachers. (Knott & Miller, 1987) The effect of this distortion is frequently a proliferation of procedures, regulations, interruptions and paperwork that impedes rather than facilitates student learning. Many teachers leaving urban districts cite paperwork and bureaucratic over regulation as among the most debilitating conditions they face.

The self-serving nature of the district bureaucracy frequently impedes initiatives, which would decentralize decision making and transfer power to individual school staffs. (McClafferty, 2000) Historically centralized systems are reluctant to change. Prodded by parents, community and business leaders, urban districts are gradually allowing more decentralized decision making at the school level. In response to bureaucratic rigidities choices are proliferating within public systems. Examples include open enrollment plans, magnet and specialty schools, schools-within-schools, alternative schools, and public choice and charter schools. Urban parents also have increased options outside the public systems through private school voucher programs but these efforts account for less than one percent of enrollment in urban districts. (Hill, 1999)

6. School Staff Accountability.

As public school options increase so do calls for accountability. The most frequently tried accountability efforts in the last century have been attempts at merit pay for teachers based on student achievement test scores. Many of these trials have been funded by private foundations and several have been supported initially by local teachers unions. Thus far, however, there have been no successful models for holding either principals or teachers accountable based on achievement scores. (Ross, 1994) In some cases superintendents have clauses in their contracts stating that their tenure or salaries are dependent on improvements in student achievement. In some districts school principals’ annual evaluations and contract extensions are now tied to improving student achievement. Currently, many states have adopted systems for declaring particular schools (or districts) as failing if a given number of the school’s students are below a minimum level of achievement. In these cases the state may mandate that a failing school be reconstituted and may grant the local district the authority to re-staff the school with a new principal and teaching staff. (Crosby, 1999) The staff of a failing school is typically permitted to transfer to other schools in the district. This means that while an urban school district is being held accountable based on achievement data the individual staff members are not. Furthermore the concept of accountability is non-existent for curriculum specialists, hiring officials, or those who appoint principals, psychologists, safety aides or other school staff.

7. Teacher Shortages.

The public clearly understand the importance of well-prepared teachers: 82% believe that the “recruitment and retention of better teachers is the most important measure for improving public schools, more effective than investing in computers or smaller class size.” (Education Commission of the States, 2000) In the next decade there may be as many as 1 million new teachers hired because of turnover, retirement and the fact that the typical teaching career has shortened to approximately 11 years. (Langdon & Vesper, 2000) If the school age population continues to increase, another million teachers may be needed. While all districts face occasional selected shortages of special education teachers, bilingual teachers, math or science teachers, the major impact of the current and continuing teacher shortage falls on the urban school districts. These are the teaching positions that many traditionally prepared teachers are unwilling to take. This problem is confounded by the fact that many urban districts must lay off teachers to make up for budget deficits in a given year while they are simultaneously recruiting teachers to remedy their chronic shortages. (Reid, 2002)

In the states that prepare a majority of the teachers in traditional university based programs more than half of those who graduate and are certified never take teaching positions. (Schug, 1997) “ One third of new teachers leave the profession within five years.” (Education Commission of the States, 2000) The typical teacher education graduate is a 22-year-old white female, monolingual with little work or life experience. She will teach within fifty miles of where she herself attended school. The profile of teachers who succeed and stay in urban school districts differs in important respects. (Sprinthall, 1996) While they are still predominantly women, they are over 30 years of age, attended urban schools themselves, completed a bachelor’s degree in college but not necessarily in education, worked at other full-time jobs and are parents themselves. This successful pool also contains a substantially higher number of individuals who are African American, Latino and male. Typically, the teacher educators who serve as faculty in traditional university-based teacher preparation programs have had little or no teaching experience in urban school districts while those mentoring teachers in alternative licensure programs typically come from long, successful careers as teachers in urban districts.

8. State Licensure Laws.

While traditional teacher preparation programs seek to attract more young people into the teaching profession, past experience suggests that many of these graduates will not seek employment in large urban school districts where most of the new hires will be needed. (Schug 1997) To assist in meeting this urban district need, new kinds of recruiting and training programs are being established to attract older, more experienced and more diverse candidates into the teaching profession. States differ widely in their response to these new programs. “Conventional wisdom holds that the key to attracting better teachers is to regulate entry into the classroom ever more tightly…” while others argue that “the surest route to quality is to widen the entryway, deregulate the processes, and hold people accountable for their results…” (Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, 1999) Forty-three states have passed alternative licensure laws which permit the hiring of college graduates who were not trained in traditional programs of teacher preparation. But licensure requirements vary greatly across the states and implementation of new approaches is often controversial even though an increasing number of urban districts now “grow their own” teachers using alternative training programs. (Feistritzer, 1993)

9. Funding for Districts and Classrooms.

Students in urban school districts often have substantially less annual per student support than they need. The level of support in urban districts, however, generally exceeds the per pupil expenditures in small towns and rural areas. Many argue, therefore, that in total there is no shortage of funds for urban schools especially when categorical aids and grants are considered. The overall problem of inadequate funding is often exacerbated after the urban school district receives its funds and distributes the monies from the central office levels to the individual schools. Too often too many funds are expended to maintain central office functions leaving too little to cover the direct costs of instruction and equipment in specific school buildings. In addition, many urban districts are characterized by buildings that are outmoded, even unsafe, creating conditions which make learning problematic. New York City, for example, has over 150 buildings still heated by coal.

10. Projectitis.

New school board members and superintendents often believe they must set their personal stamps on the district through new initiatives. It is common for urban districts to claim they are aware of and experimenting with the latest curricula in reading, math, science, etc. (Schuttloffel, 2000). In addition, administrators are pressured to try out new programs against drugs, violence, gangs, smoking, sex, etc. This proliferation of programs and projects results in so many new initiatives being tried simultaneously it is not possible to know which initiative caused what results. Furthermore, not enough time is devoted to the program to give it sufficient time to demonstrate intended results. The problem is compounded by the fact that many of these new initiatives are not systematically or carefully evaluated. Veteran teachers, when confronted with the latest initiative from the school board or administration, typically become passive resistors. “This too shall pass.” The constant claims of experts, school boards and superintendents that their latest initiative will transform their schools is frequently stonewalled by the very people who must be the heart of the effort for it to succeed. (Van Dunk, 1999)

11. Narrowing Curriculum and Lowering Expectations.

As presented in state and local district philosophy and mission statements the list of what the American people generally expect from their public schools is impressive. A typical list is likely to include the following goals for students: basic skills; motivated life long learners; positive self concept; humane, democratic values; active citizens; success in higher education and in the world of work; effective functioning in a culturally diverse society and a global economy; technological competence; development of individual talents; maintenance of physical and emotional health; appreciation and participation in the arts. In many suburban and small town schools the parents, community and professional school educators maintain a broad general vision about the goals that 13 years of full time schooling is supposed to accomplish. But in the urban districts serving culturally diverse students in poverty these broad missions are frequently narrowed down to “getting a job and staying out of jail.” (Russell, 1986)

Narrowing down the curriculum is particularly evident among the burgeoning populations of students labeled as special or exceptional. The urban districts have disproportionately large and wildly accelerating numbers of students labeled with some form of disability. In urban districts the numbers of special students currently range from 6% to 20% of the student body. This means that exceptional education may account for between 20 and 35% of a total urban district’s budget. Well intentioned but sometimes misapplied state and federal initiatives for special education students encourage the labeling of increasing numbers of students as learning disabled, cognitively disabled or having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. (Breggin & Breggin, 1994) It is not uncommon for many urban teachers who do not have in depth knowledge of child development to perceive undesirable behavior as abnormal rather than as a temporary stage or as student responses to poor teaching. Thus it is common in urban middle schools to find many students doing well academically who have been labeled as disabled in primary grades and who will carry these labels throughout the remainder of their school careers. Teacher expectations are likely to be very modest for such children; testing may be waived. Some low-income parents may be enticed to agree to have their children labeled exceptional because of financial grants. Recent efforts at inclusion for exceptional students in regular classrooms are aimed at breaking the cycle of low expectations and isolation. In urban districts, however, inclusion mandates are most frequently followed in the primary grades but seldom at the high school level. (Cohen, 2001) The disproportionate number of children of color, particularly males, labeled exceptional further exacerbates this problem.

12. Achievement and Testing.

There are four curricula operating in schools. The first is the broadest. It is the written mission of the school district. The second curriculum is what the teachers actually teach. The third operative curriculum is what the students actually learn which is considerably less than what the district claims or what the teachers teach. The fourth curriculum is what is tested for and this is the narrowest of the four. The tested for curriculum frequently supports the narrowing and lowering of expectations. (D’Amico, 1985) As total school and district programs are evaluated by norm referenced tests the accountability of teachers and principals is also narrowed and lowered to the kinds of learning that can be readily tested. Recognition of this problem has led to a new emphasis on standards-led testing or performance assessment closely linked to curriculum in place of the norm reference testing that compares student’s performance to that of others. Done carefully, such assessment measures the performance of successive cohorts of students against an annual rate of improvement (local or state) that is sufficient to achieve whatever curriculum goals have been set. (Education Commission of the States , 1997) For the most part, aligning the goals, curriculum, instruction and testing is yet to be accomplished.

The Haberman Educational Foundation in its article shows a detailed information about the characteristics of the U.Ed. students and their characteristics as well as a huge list of references.

Urban Education and Movies

Looking for information in the world-known browser "google", I´ve found something really interesting: one article that talks about the urban movies whose common denominator is how their characters, urban teenagers, struggle in unstable environments.

One of my favorite is "Dangerous Minds" with an excellent sound track.

What´s your favorite movie? You can choose your movie clicking here.

Now that I´m talking about that movie set in the mid 1990s, another thing caught my attention. If all those problems were already happening in that period, what has changed? So, again back to google and I try to look more information about U.Ed. and found this interesting article

A New Era in Urban Education? where we can read many characteristics of the schools and students of that period that are still happening 20 years later. Those issues that are present in our schools are the challenges to deal with low-income students and families, but there was a new topic: "charter schools" that according to the ideas of the year of the article (1998) these schools would give an answer to their problems. I don't want to go on talking about charter schools because it´s a topic that we will deal with during our second session. Be patient!

References and articles

- http://www.right-to-education.org/page/understanding-education-right

- https://learningandurbaneducation.wordpress.com/